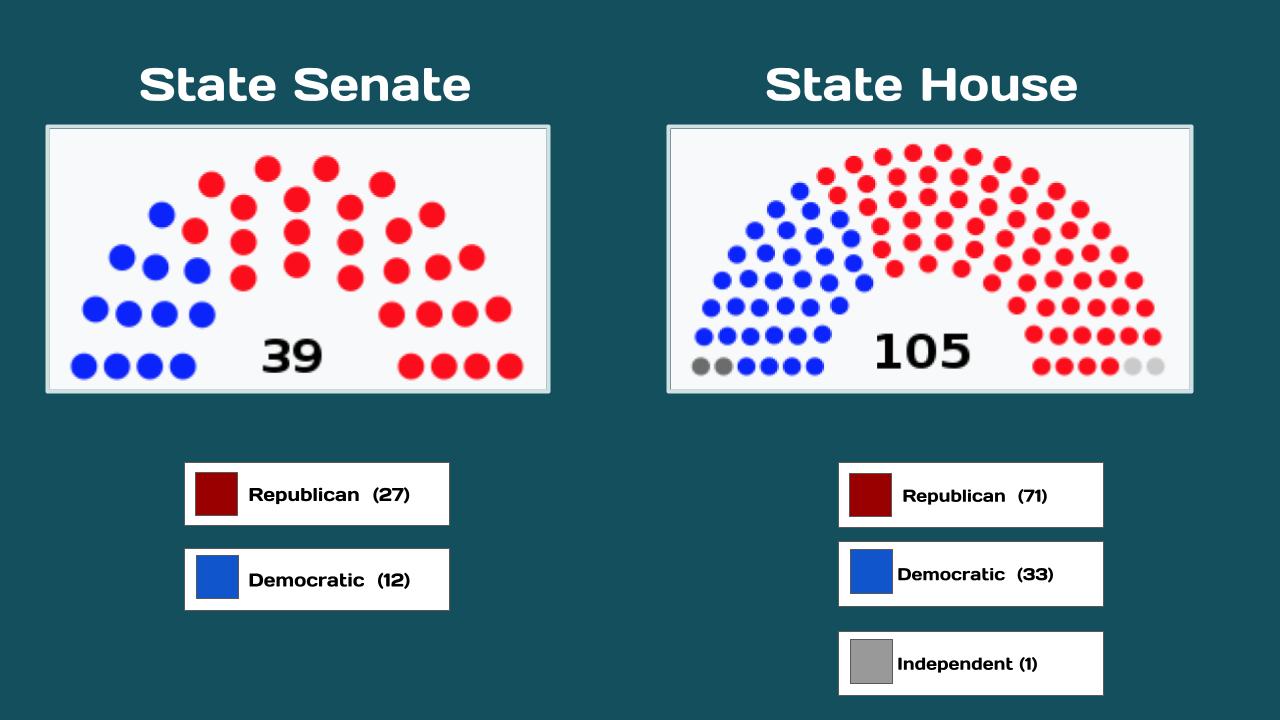

The Louisiana State Legislature is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Louisiana. It is a bicameral body, comprising the lower house, the Louisiana House of Representatives with 105 representatives, and the upper house, the Louisiana State Senate with 39 senators. Members of each house are elected from single-member districts of roughly equal populations.

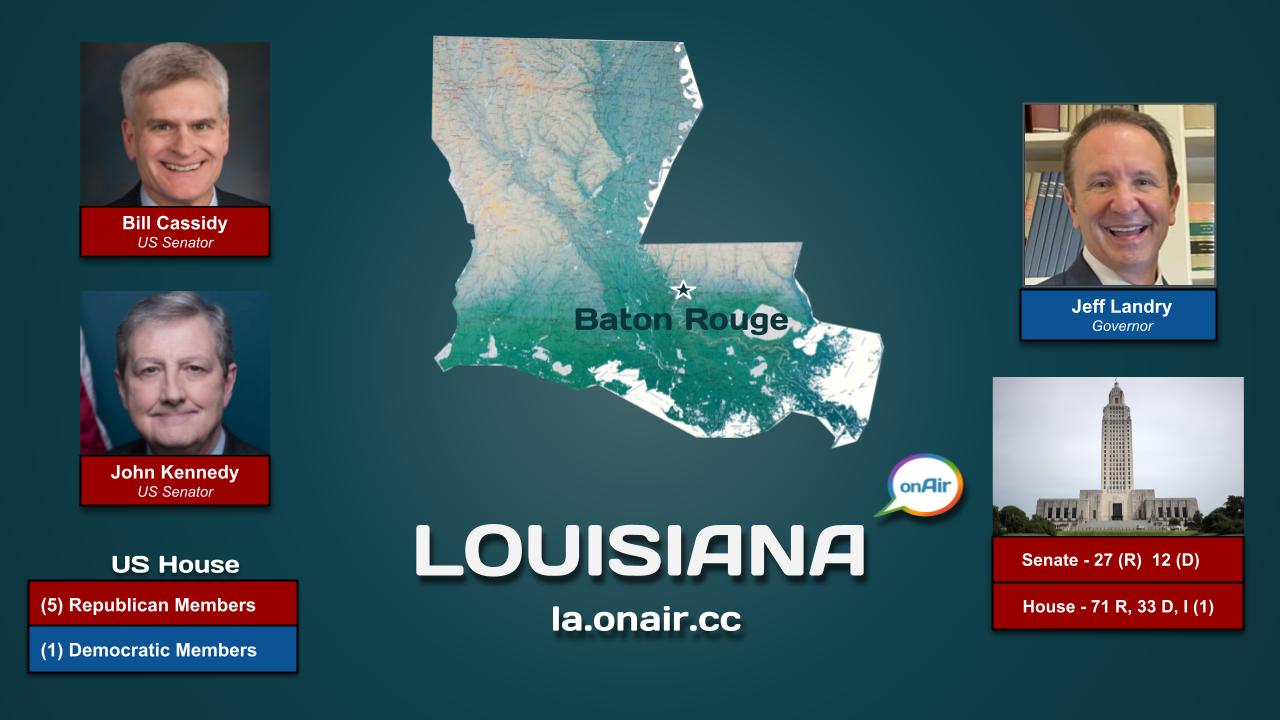

The State Legislature meets in the Louisiana State Capitol in Baton Rouge.

OnAir Post: Louisiana onAir